Prelude: The Legend of the Giant Antaeus

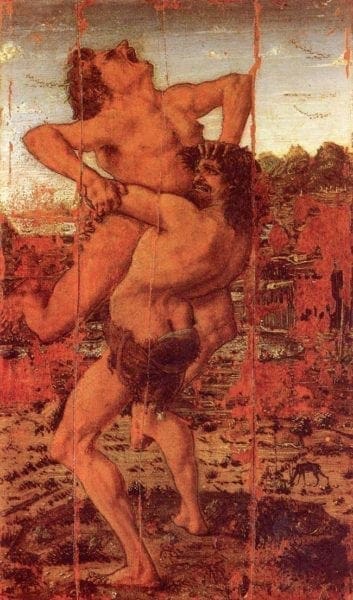

These days we all, as individuals and as a collective, seem to be like the giant Antaeus from Greek mythology. He was the son of Poseidon, the god of the sea, and Gaia, the personification of the earth, and had virtually invincible strength.

When Heracles met the giant he was challenged to a fight and an unequal trial of strength began. However much Heracles struggled he could not overpower Antaeus because he kept getting new energy and healing from the earth. Only when he was lifted up in the air, was he robbed of his strength and defeated. He had the ground pulled from under his feet, in the true sense of the phrase, and therefore lost his connection to his mother, Gaia.

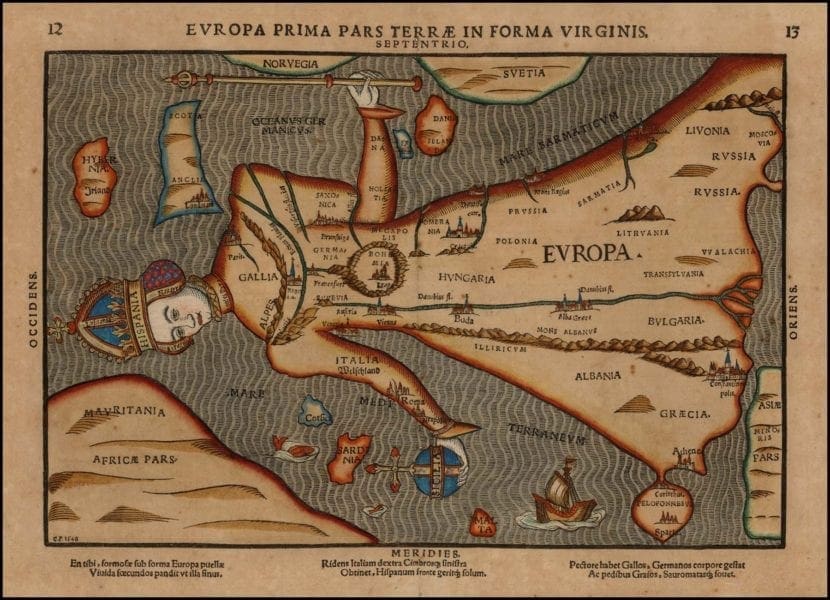

This picture can be further developed. The ground on which we stand and from which we originate is always historical. Not only soaked in history, but also in itself an expression of this. Our clothing, language, indeed every word, all sorts of things have grown and been cultivated historically. An insight into these processes is at the same time an experience of freedom and education, and thus a strengthening of one’s own identity. The crisis in which Europe currently finds itself can also be most conclusively described as an identity crisis. Insecurity regarding personal values, misunderstood, stark liberalism, which offers no orientation and leads to relativism, plus the invisibility of one’s own evolution or ‘becoming’, are just some of the symptoms and reasons for the present situation.

Europe as something common and shared should be understood as the European cultural consciousness. It is a social space, a storeroom of common ideas, forms, (hi)stories and enthusiasms. Pursuing and presenting these is the task and concern of the international research and exhibition project Mnemosyne, for a sense of history is grounding the present in the past.

Identity is based on History and Stories: the Necessity of a Positive Narrative

It is important to recognise that a national identity is formed in a similar way to a personal identity: narratively. Whilst talking about oneself engenders the identity of a person, communities create their identities through stories. This occurs through the handing down of memories with a national, or in Europe’s special case pan-European, reference. Europe, however, lacks these broad-based, common positive stories. Pro-European sentiments are usually argued on the basis of the absence of things (e.g. no war, no border controls, no currency exchange etc.). This is correct, but citizens have become accustomed to this state and, for the younger generation in particular, it hardly has any identity-conveying potential. Moreover, nobody falls in love with an internal market.

These days more urgently than ever, we need a common and, above all, positive memory culture, a new pan-European self-image over the web of one’s own story, on the basis of which a future social and political togetherness can succeed. For in point of fact, the world repeatedly empties itself during the changing of generations and endless stories, which are connected to places and objects and are inevitably lost. The idea of a common cultural identity is necessary to counteract this automatic and insidious memory loss, which society barely notices. Culture transcends national borders and ultimately creates itself through comprehending and identifying its own past, healing and accepting, the recognition of differences and appreciation of the complexity of its own and the other.

The Inhabitants of a Dream

Europe is a normative utopia, the desirable unity of inner community and humanistic, social and democratic values. The European utopia of peace and coexistence of different cultures and states did not arise beyond history, but is the direct answer to a history of war and conflicts. A terrible influence, which first led to thoughts of unity.

The Mnemosyne project is thereby part of a larger movement of a historical and identity-political search. This found its most prominent expression in the declaration A new narrative for Europe: The Mind and Body of Europe and was presented in the presence of the then President of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso, and the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, in Berlin on 1st March 2014. In this declaration, developed in dialogue form by leading worldwide artists, philosophers and scientists, some of whom will also be present at the exhibition, is this statement, amongst others: ‘[T]he cultural inheritance of Europe is the continent’s most sustainable resource …’

Reminiscences from the Mortuary - Remembering as a peaceful process

In conclusion, we would like to emphasise that Europe – whether that of the cultures, regions or national states – draws its wealth from diversity and heterogeneity, which sometimes entail divergences right up to incompatibility. Yet the links within this very amalgam and tense relationship should be sought and represented. Unlike projects appearing at first sight to be similar, which confront a commemorative question, Mnemosyne will not concentrate on Memories from the House of the Dead – the title of the epilogue in the book Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 by the great British historian Tony Judt (2005).

The exhibition is rather concerned with showing that history can also be understood in a different way, and that identity should be defined through positive narrative. The past is not purely an expanse of ruins. When the exhibition begins, Western Europe will have enjoyed almost 75 years of peace. A lifetime. The past should be perceived and accepted as living memory, as a treasure and richness, offering orientation as well as admonishing.

»He who cannot remember the past, is damned to repeat it.« Of course the sorrowful stories of war and displacement, the Shoa, torture and violence, will and must find their place in the exhibition. However, they will emerge as one amongst many determinants of our common memory. Remembering can be a joyful process, as well as a painful one. Both aspects are necessary.

Mnemosyne’s fundamental objective is, to put it in a nutshell, fostering relationships; a relationship to the past, to the present, to one’s own identity and future. Each visitor should be able experience these in a personal way and confront them with multiple vibrancy. The past not as an abstract, but as the subject of interest, passions, indeed even a certain ‘fan culture’. This is also the purpose of the various games, possibilities for participation, the avatars and patrons, the use of comics, virtual reality, workshops and other media and offers. It is our profound conviction that participation and identification (figures) are the easiest and most sustainable ways to learn about culture.